The HOPE Best Practice Network comprises twelve social history institutions across ten countries and is a representative sampling of social history institutions in various organizational and socio-political contexts. All are members of the International Association of Labour History Institutions (IALHI). HOPE partners include:

- Amsab-Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis, Ghent (Amsab-ISG)

- Bibliothèque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine and the Musée d'histoire contemporaine BDIC, Nanterre/Paris (BDIC)

- Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro, Rome (CGIL)

- Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Bonn (FES)

- Fundação Mário Soares, Lisbon (FMS)

- Génériques, Paris (Génériques)

- Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis, Amsterdam (IISG)

- Maison des Science de l'Hommes de Dijon et le Centre Georges Chevrier, Dijon (MSH-Dijon)

- Open Society Archives at the Central European University, Budapest (OSA)

- Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv, Zürich (SSA)

- Työväen Arkisto, Helsinki (TA)

- Verein für Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, Vienna (VGA)

HOPE social history partners, also called HOPE content providers, are for the most part private or non-profit organizations with independent legal status or only loose state controls; only three are completely state funded. While most stand as independent legal entities, they can nevertheless be highly dependent on the level of the national digital strategy (as BDIC is on Gallica, Amsab-ISG is on MovE – Musea Oost-Vlaanderen in Evolutie, FES (AdsD) is on the Bundesarchiv portal, and TA is on the Finnish National Digital Library); encompassed by state entities (as BDIC is by BnF – Bibliothèque nationale de France, MSH-Dijon is by the CNRS – Centre national de la recherche scientifique, IISG is of KNAW – Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, or VGA is of the Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv); or part of the higher educational sector (as OSA is of CEU–Central European University, CGIL is of CNR–Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, MSH-Dijon is of the Université de Bourgogne, or BDIC is of the Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense). Only a few, such as FMS or Génériques, are truly stand-alone organizations.

Most social history institutions consider external cooperation an essential part of their organizational mission, though such activities are not always well integrated into everyday operations. There are numerous forms of collaboration with a varying scope: union catalogues, cooperative digitization projects, shared infrastructure, and business partnerships to provide services or support. Local networks, strategic funding, long-standing commitments, and infrastructure generally take priority over international projects, which often survive for a couple of years. Strategic partners and networks can form a community with almost as strong claims as an institution's target community of users. Though state funding is generally provided in limited measure, many also depend on funding from private resources and donations.

Policies and Planning

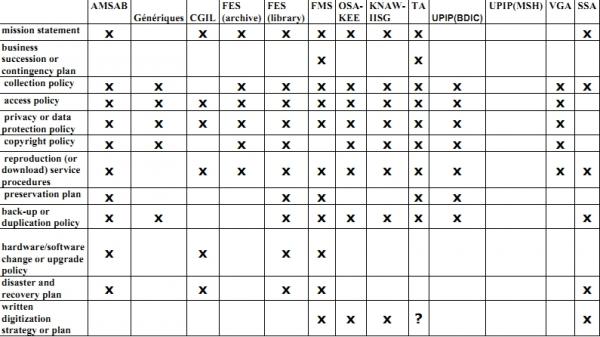

Table 1-A - HOPE Content Provider Policy and Planning Documents: policies, planning documents, and written procedures identified by HOPE content providers. Categories were established with the help of Trusted Digital Repository toolkits: Drambora and TRAC.

As can be seen from Table 1-A, almost all HOPE content providers possess a mission statement of some sort. Surprisingly, based on survey responses it seems that the French partners and VGA do not. Disaster recovery, contingency planning, and other key documentation are also neglected according to survey data. Seen in a certain light, this data highlights the difficulties in assessing organizational policy frameworks in the context of complex institutional arrangements. Such complexities are common at social history institutions as many of these entities are integrated into state bodies or academic networks; custodianship is often undertaken at a higher level, and not always visible or well articulated at the level of the social history institution. The case of MSH-Dijon, a highly embedded organization, is illustrative in this regard. Staff confirmed in interviews that they have no written policies of the type listed in the survey. Their administrative policies and procedures are set at the university level. Their professional practice is guided by the French and international archival standards and guidelines. They follow the national guideline TGE Adonis for digitization.

Seen in another light, missing policies might also reflect a lack of long-term vision and strategy. The fact that only two HOPE content providers were aware of business succession or contingency plan and five content providers of preservation plans does not bode well. Reviewing the list, it becomes clear that institutional policy framework focuses on the here and now. Collection policies, access policies, privacy or data protection policies, copyright policies, reproduction service procedures, and back-up or duplication policies all score highly. This is the set of policies needed to run routine operations and day-to-day user services. Long-term organizational viability is not addressed.

Digitization plans or strategies were noticeably scarce, surprising given these institutions' clear focus on digital content (signaled by their participation in HOPE). Looking more closely at the possible types of digitization, 1) large-scale systematic digitization, undertaken primarily for preservation, 2) project-based or small-scale digitization, primarily for access, and 3) on-demand or ''ad hoc'' digitization, generally as an internal or external reproduction service, social history institutions strongly favor the short-term goals of small-scale projects. Eleven content providers listed access as a reason for digitization. Seven also listed preservation as a factor, yet as can be seen, only four had a documented digitization plan or strategy.

Digitization priorities are, in fact, often set in the context of external commitments. MSH-Dijon are currently working on a digitization project with l’Institut National des Appellations d'Origine (INAO, the organization charged with regulating French agricultural products). IISG worked closely with the Koninklijke Bibliotheek to digitize brochures and other material. OSA cooperated with Columbia University's Butler Library to reunite a collection on Hungarian refugees after 1956. FMS are involved in several ongoing projects, including those with the Assembleia Nacional de Cabo Verde, the Arquivo Histórico Nacional de Cabo Verde, and the Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisa (INEP). And BDIC are regularly involved in thematic digitization projects with the BnF.

Outsourced digitization is common. Many institutions mix in-house and outsourced digitization depending on the nature and time constraints of a particular project. Three HOPE content providers outsource all digitization activities, while seven mix in-house and outsourced digitization. With outsourcing comes risks; a loss of control over the quality and conditions of digital reproduction; and a potential loss of control over rights to material, especially with advanced digitization and enhancement techniques. Social history institutions may be unaware of the potential risks of outsourcing these activities.

More troubling may be the lack of concern over long-term system viability. While routine back ups are clearly taken seriously, HOPE content providers seem to lack a vision (or at least a documented vision) for their technical infrastructure and moreover seem to ignore the potential risk of disaster to their collections, facilities, and even staff. In this case as well, there is an increasing tendency to rely on external technical infrastructures for storing, backing up, and recovering digital content, again removing control and oversight from the institution itself. At least five HOPE content providers rely on external or supra-infrastructures for secure storage of digital masters and back-up of databases. It remains unclear whether institutions confirm that policies and procedures followed offsite meet institutional, community, and donor requirements, and if so, whether such arrangements are cemented in formal agreements. Securing and safeguarding content is a first line of defense. And when it is a question of born-digital content or content that exists only in digital form, it is an imperative.

Social history institutions often see it as their mission to protect rare private collections, or to rescue and secure endangered archives, or to safeguard politically sensitive material. Back-up policies and levels of disaster preparedness are, in fact, closely linked to this mission, having a real impact on institutional reliability among many other things.

Emerging Business Models

All this raises questions as to whether the business models currently followed by social history institutions are sufficient to support strategic planning in a more comprehensive manner. Or to be more precise, whether the development of digital services fits into the current business model. During interviews, content providers complained of a continuous dilemma over where to invest resources and how to prioritize between analogue and digital services. Many also confirmed that digital services are still viewed as an extension of their analog counterpart, and therefore play a less integral role in daily operations. New systems seem to exist in uncomfortable parallel with legacy systems. This constant balancing between 'types of services' reveals an ''ad hoc'' approach as well as a lack of strategic thinking.

On the one hand, social history institutions with an aim to serve their publics and fulfill their non-public mandate, are feeling pressure from the growing number of users who have moved online and who have high expectations to be served online. Institutions feel compelled to offer up content and services on social sites, such as Flickr, Facebook, and Scribd, as well as on cultural heritage portals like Europeana. It is thus not surprising that several HOPE content providers have turned out to be early adopters of new user-centered technologies and services. FES (AdsD) ran a crowd sourcing project, uploading selections from their photo collection to Wikimedia under a Creative Commons non-commercial, no derivatives license. OSA developed the Parallel Archive, a collaborative digital humanities tool allowing users to upload and form communities around archival sources. Génériques created thematic blogs ''Melting Post'' and ''Génération'' to explore topics of interest using sources from their collection. On their ''Hoje no século XX'', FMS provide dynamic feeds of newspaper headlines from throughout the last century. On the other hand, social history institutions are increasingly compelled to compete for funding subsidies to support this work. And there is as yet no clear evidence that such temporary non-structural funding can sustain their growth online over the long term.

Yet this situation may prove an incentive for experimentation with new entrepreneurial approaches to digital services in order to recover some of their costs. IISG may be a forerunner of the next wave with their Social History Shop, which combines the best features of a library search engine and an online retailer to offer up high quality reproductions of original archival content.

HOPE Recommendations

To help content providers address these issues, HOPE recommends the use of a Trusted Digital Repository self-audit toolkit, such as TRAC, DRAMBORA Toolkit, Nestor, the Data Seal of Approval, or the Data Asset Framework (DAF). The ultimate goal of this effort should be that the institution can:

- articulate and document its own missions, aims and objectives, shortcomings and potentials;

- inventory its activities and assets;

- and be aware of pertinent risks and try to resolve these.

Social history institutions, like many other cultural heritage institutions, are in the transitional phase between traditional collection management and digital object management. Yet taken together, the digitization of analog collections, storage and management of content, and expanded access do not form a break with former practice but an extension of it. These institutions will continue to serve their designated communities in a traditional way, offering records physically in their reading rooms or on offline networks to comply with legal regulations. It is also true that digitization and digital curation is a costly endeavor and not all analog collections need to be digitized. Therefore prioritization and planning remain an issue. The audit process would allow these institutions to analyze their strengths and weaknesses and to respond in a systematic fashion as part of their high-level business planning.

Related Resources

''Data Asset Framework (DAF)'' (http://www.data-audit.eu)

''Data Seal of Approval'' (http://www.datasealofapproval.org)

''Digital Repository Audit Method Based on Risk Assessment (DRAMBORA)'' (http://www.repositoryaudit.eu)

Nestor Working Group for Trusted Repositories. ''Catalogue of Criteria for Trusted Digital Repositories, Version 1''. Frankfurt Am Main: Network of Expertise in long-lerm STORage, 2006. (http://files.dnb.de/nestor/materialien/nestor_mat_08-eng.pdf)

RLG-NARA Task Force. ''Trustworthy Repositories Audit & Certification: Criteria and Checklist, Version 1.0''. Dublin, Ohio: OCLC, February 2007. (https://www.crl.edu/sites/default/files/d6/attachments/pages/trac_0.pdf)

RLG-OCLC. ''Trusted Digital Repositories: Attributes and Responsibilities''. RLG-OCLC Report. Mountain View, Calif.: RLG, May 2002. (https://www.oclc.org/content/dam/research/activities/trustedrep/reposit…)

''Très Grand Equipement Adonis (TGE Adonis)'' (http://www.tge-adonis.fr)