The sheer range of currently held analog and digital material and the several workflows for managing this material present a real challenge for legal compliance. The holdings of a given social history institution may cover a range of content formats, among these "archives, books, periodicals, brochures, leaflets and pamphlets, visual documents such as posters, prints, cartoons and photographs, audiovisual and sound recordings, banners and paraphernalia." And digital material is no less varied—whether it be digitally-born or digitized content; a simple image file scanned in the 1990s, a database from the 1980s, or a complex multimedia object created very recently; a proprietary or an open format; a preservation quality master object, a watermarked access copy, or a thumbnail. Social history institutions working in peculiar conditions to digitize unique collections or to accession externally digitized materials have little control over formats and quality; however, they are in control of statutory provisions, deeds of gift, donation agreements, and licenses that eliminate ambiguity in the ownership and reuse of collections.

As seen in Organizational Framework: Governance and Viability, most institutions have a developed set of in-house legal policies or have adapted policies set by major cultural heritage entities. Eleven HOPE content providers have data protection or privacy policies, while nine have copyright policies. Still, these policies generally focus on the management of analog material, while the status of digital materials often remains unclear. Moreover, when content providers were asked whether "they know about digital donations" and whether "the current policy framework treats sufficiently content existing only in digital format", several admitted to being involved on projects when another organization donated only digital copies to them with no special provisions or when digital content was given away with no legal stipulations. Quite a few content providers suggested that digital records were merely copies of physical records, and as such deserved no special status—although IISG, FMS, SSA, and OSA have already started accessioning digitally born materials.

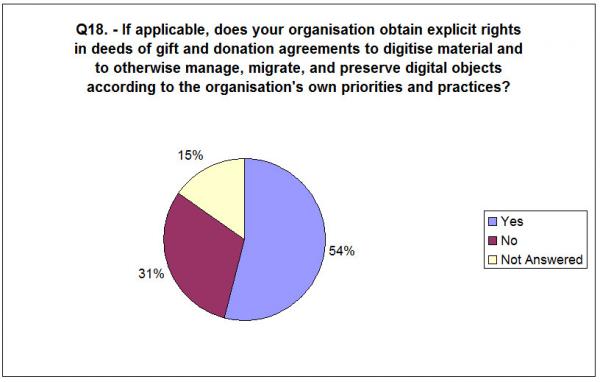

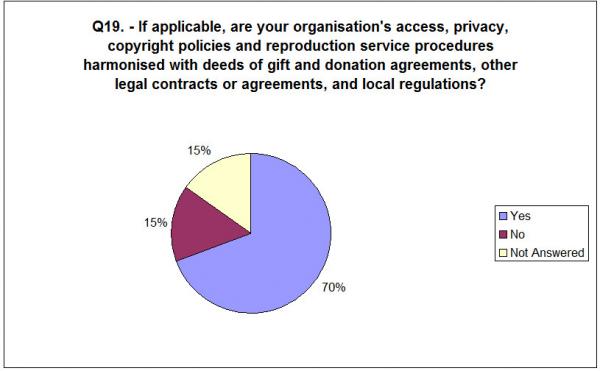

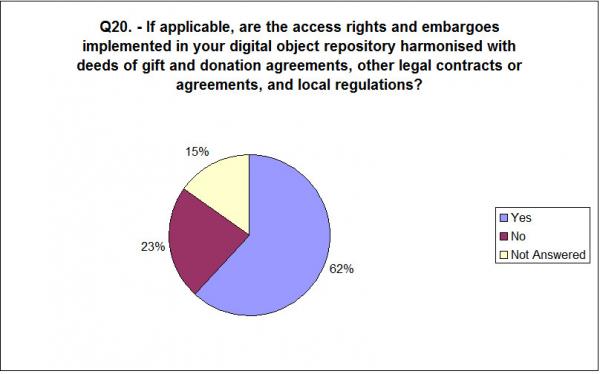

Charts 1-B, C, and D - HOPE Content Providers Obtaining and Harmonizing Rights with Policies and Access

Both the survey analysis and numerous contradicting statements during follow-up interviews indicated that rights over both digitized and born-digital content are not addressed in a comprehensive manner at many partner institutions. As shown in Chart 1-B, only 54 percent of HOPE content providers obtain specific rights to digitize material and manage digital copies. Chart 1-D indicates that 62 percent actually harmonize the rights they obtain over digital content with access conditions (23 percent explicitly state that these are not harmonized).

Legal Barriers to Access and Reuse

It has become crucial to expand the practice of 'due diligence' beyond our physical collections. The following problem areas have been identified:

- *Deposit agreements and deeds of gift often impose restrictions, so-called donor restrictions, that go beyond national legal requirements and can include lengthy embargoes on public access to material. On the other side, donors often hold the rights only over the physical objects as property but not the intellectual property rights (IPR). As such, they have no power to grant copyrights or licenses on donated materials.

- Clearing rights on copyrighted and orphan works is a burden on social history institutions with their limited resources and broad collection scope. Exception-based copyright legislation cannot be effectively applied over collection-based solicitation; a single collection may consist of different types of materials with different copyright holders.

- Compliance with data protection laws is an additional obstacle as social history collections by their nature include sensitive data about private people.

- There is no standard licensing regime available for private repositories wishing to publish materials online.

- Social history institutions often fail to obtain the rights to transform material for preservation purposes. Moreover, responsibility for preservation has traditionally been considered as attendant on ownership of analog files. The responsibility that comes with ownership of less-tangible digital material is less clear cut.

- Digitization for preservation is not clearly distinguished from digitization for distribution and public use. On the other hand, large-scale digitization involving third parties, even with the goal of preservation, might raise copyright concerns.

The legal barriers to access and reuse of material remain high. A majority of HOPE partners list IPR as an obstacle to their work. Six content providers explicitly remark the presence of orphan works in their collections, often in large quantities. For those whom IPR is less of a problem, third party privacy has been an issue. One content provider also mentioned 'secrecy' laws in the case of state documents.

Implementing Rights

As noted above, the connection between rights held and access given is tenuous and heavily dependent on informal practices or manual intervention. HOPE content providers confirmed that copyrights and other legal restrictions are the main basis for regulating access to digital and analog content. Yet information on rights and restrictions is stored in local systems as loosely-controlled free-text metadata—a practice which served for physical materials but does not extend well to online publication. Access is often controlled at a high level (fonds, series, serial) and through informal procedures. In lieu of granular access rights management, restrictions are often reflected in digitization priorities, as potentially problematic collections are not digitized in the first place. In the most extreme cases, digital collections are available only onsite.

When access to digital content is given, HOPE partners limit its reuse primarily through physical barriers, such as the provision of lower quality derivatives and watermarked copies. Licenses or legal clauses stipulating permitted uses are offered as part of reproduction services, but not for material presented online. With such informal practices, it can be surmised that if in doubt, or simply for convenience, institutions rather err in the direction of over-restricting their collections. It is telling that Amsab-ISG, OSA, and MSH-Dijon are the only three content providers who mention institutional opt-out policies.

HOPE Recommendations

As a rule, social history institutions disagree with the current exception-based copyright regime, which does not take into consideration the unique value of historical collections as a whole and their importance for research and educational use. These institutions consider their activities—providing both short- and long-term access—a public and non-commercial service. There is a general consensus that notice and take-down policies, in other words an opt-out model, would be more appropriate. In this case, out-of-print publications, orphan works, or works of unknown copyright status could be put online. When copyright holders were known, institutions could make a best effort to clear the rights, giving several licensing options to copyright holders, among them Creative Commons licenses or no limitation at all.

HOPE recommends that institutions clarify the permitted re-use of online materials prior to works being put online, and include them in the donation agreements, which should be harmonized with licensing regimes. Rights management should be folded into routine accession and processing/cataloging workflows and machine-actionable data should be captured in collection management and digital repository systems at a high level of granularity. Rights management should cover digital and physical copies without discrimination.

What remains to be tackled is access and curation in the longer term. Professional attitudes towards digital curation and digital repository management must change; digital materials should be understood as more than copies of physical collections and an integrated approach to material in its multiple formats should be formulated. Most social history institutions have strong opinions about access to their collections in the short term with some ideas for addressing it. HOPE content providers have shown themselves willing to comply with the legal requirements set by the European Commission and Europeana, carefully selecting openly accessible collections and assigning Europeana licenses to digital materials. However, social history institutions must also take care to secure the rights to manage material, in whatever format, over the long term.

Related Resources

The European Digital Libraries Initiative. ''Sector-Specific Guidelines on Due Diligence Criteria for Orphan Works (Joint Report)''. (ca. 2008). (http://www.europeanwriterscouncil.eu/images/pdf/digitallibraries/11guid…)

Keller, Paul. "Copyright." In: ''Business Model Innovation Cultural Heritage''. Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science: Amsterdam & The Hague, 2010. (https://www.kl.nl/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/kl_busmodin_web_eng_2.pdf)